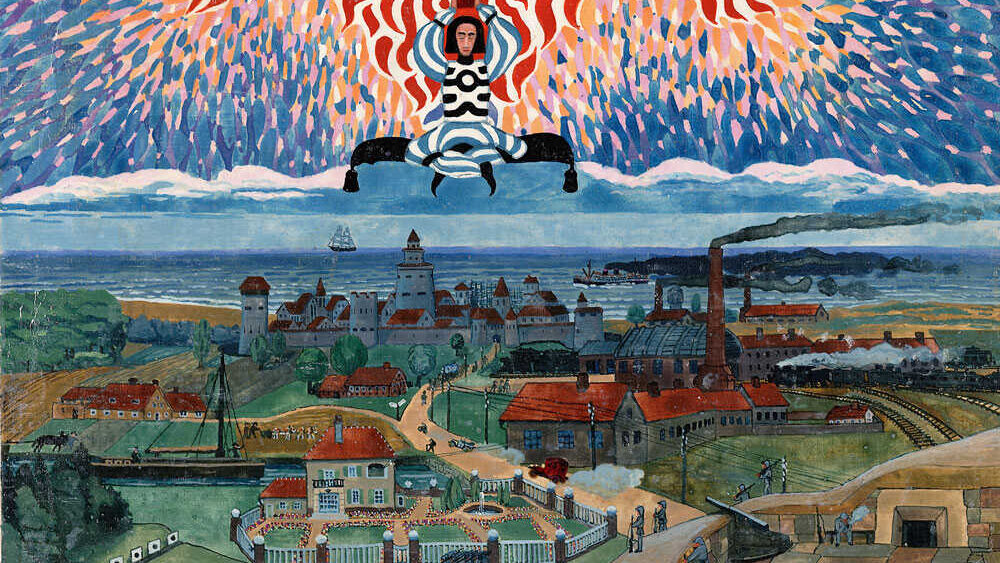

Detail of an original artwork by Carl Jung, from his Red Book (Liber Novus)

What is the difference between the part of the mind we are conscious of and the part we are not, and why is that distinction important?

In the previous post i mentioned that Jung’s philosophy can offer you a map of your own mind, which is incredibly useful in everyday life. Before we can really see what the map is like, we will need a couple of posts explaining basic Jungian concepts. Arguably, the subject of this post will be the most fundamental for your entire understanding of Jung’s philosophical system.

From a Jungian perspective, there are two main faculties within the mind. There is a conscious facet and there is an unconscious facet. The conscious mind represents what we are actively aware of, while the unconscious consists of thoughts, instincts, and processes generally hidden from us. Consciousness is thus essentially awareness: an awareness of phenomena within us and around us. This is illustrated in the following example by Murray Stein:

A friend observing the birth of his daughter told me how moved he was when, after the placenta was removed and her eyes cleaned, she opened [her eyes] and looked around the room, taking everything in. This was clearly a sign of consciousness (Stein, 1998).

In contrast, Jung refers to the unconscious as “the unknown of the mind” (Jung, 1951), a realm beyond our immediate perception that still plays a significant role in our actions.

This distinction itself is often already controversial, as many philosophical and cultural perspectives—especially in Western thought—tend to presuppose that individuals have full, rational control over themselves. This is engrained in our laws and even the very form of our government. This is however highly questionable. Consider the example of the ‘Bouba/Kiki effect,’ a phenomenon consistently demonstrated in sociological experiments. In this experiment, participants are shown two shapes—one with sharp, angular edges and another with soft, rounded curves—and are asked which nonsense word, “bouba” or “kiki,” they associate with each. Time and again, participants, regardless of cultural or linguistic background, link “kiki” to the prickly shape and “bouba” to the rounded one (Ćwiek et al., 2022).

While the exact origin of this association may stem from linguistic and sociological factors, the real point of interest here lies in what this phenomenon suggests about our minds. It hints that certain sounds or words connect to specific shapes in our minds without our conscious awareness. This raises an essential question: if we lack conscious access to this knowledge, how does it nonetheless shape our behavior? For example, how does an unconscious link between sounds and shapes influence our actions, such as naming or describing those shapes, even if we’re unaware of the association?

Another example of the unconscious mind lies in the body’s intricate communication with the brain. Modern medicine reveals that the brain is constantly receiving and processing signals from across the body through an extensive network of nerves. Much of this sensory input, however, operates below the threshold of conscious awareness. For instance, the brain is continually informed about processes like gut motility, autonomously monitoring and regulating them without our active awareness. This information remains inaccessible to our conscious mind, as it is managed by the brain independently. What’s fascinating is that research indicates that gut bacteria may influence the development of mood disorders, largely through their impact on serotonin, a neurotransmitter closely linked to mood regulation (Margolis, 2021). Our affect and our emotions hence do not seem to be fully under our rational control.

Then there are also stimuli that are not normally conscious, but which we can become aware of and regulate consciously. Consider, for example, breathing. Normally, breathing takes place without a person being aware of it, but once a person becomes aware of their breathing, it takes its place within active consciousness. This shows us that some phenomena occur on the threshold between consciousness and unconsciousness, and that focus on the phenomenon as it occurs can shift the control over it towards the Ego.

All of these examples illustrate a clear distinction between the phenomena within our minds over which we have conscious control and those that operate beyond our awareness. While certain mental processes are accessible to our conscious will, there are countless others—like the automatic regulation of bodily functions or unconscious associations—that function independently of our conscious control. In other words, these examples reveal that we have far less influence within our own minds than we might assume.

What exactly is consciousness?

Somehow, biology has made the brain capable of consciousness. It has endowed us with so much cognitive capabilities that we can actively reflect on our own actions, our own emotions and even our own thoughts. Consciousness, however, is not unique to humans. After all, animals are also aware of their environment. According to Jung, what does distinguish humans from animals is that humanity has an ‘Ego-consciousness’ at its disposal. Within Jungian theory, the Ego, the central guiding centre of consciousness, is considered “a person’s experience of himself as a centre of wanting, desiring, reflecting and acting” (Stein, 1998). Thus, what the Ego primarily does is reflect on experience, in order to determine how the individual relates to this experience. In this context, then, the Ego essentially acts as the mirror in which experiences are reflected. Experiences are made psychic, presented to the Ego, and the Ego reflects on them and acts accordingly.

Although the Ego is by definition a factor within consciousness, the term ‘Ego’ does not refer to the totality of consciousness; in fact, non-Ego consciousness also exists. An example of this is an individual’s focus while driving. An individual may be primarily engaged in a conversation in the car while also driving. In that case, the Ego focuses its attention on the conversation, while the rest of the non-Ego consciousness is busy driving the car (Stein, 1998). Both actions require high levels of information processing and awareness, but the Ego determines where its attention is focused and thus which actions are primarily evaluated. In this case, driving the car is experienced as ‘automatic’ and is not (actively) reflected upon, just until something happens that requires a redistribution of focus. What distinguishes this from a wholly unconscious act is the fact that the individual perceives themselves to be driving the car (conditional to the earlier definition).

In conclusion, a basic understanding of the psyche requires us to differentiate between consciousness and the unconscious. Jung’s concept of the unconscious as “the unknown of the mind” shows that there is a vast and largely uncharted part of our mental life that operate beyond our active awareness, influencing our decisions and behaviors. The Ego, as the central guiding force within consciousness, plays a crucial role in reflecting upon and interpreting these experiences, but it is not the totality of consciousness. Jung’s ideas about non-Ego consciousness, illustrated by phenomena such as automatic actions during driving, reveal the layered and multifaceted nature of our awareness. In future chapters we will take a closer look at the contents of the unconscious, and what those contents can do and mean.

References:

Jung, C. G. (1951). Aion – Researches into the phenomenology of the Self (2nd ed.). Routledge publishers.

Stein, M. (1998). Jung’s Map of the Soul. Open Court.

Ćwiek, A., Fuchs, S., Draxler, C., Asu, E. L., Dediu, D., Hiovain, K., Kawahara, S., Koutalidis, S., Krifka, M., Lippus, P., Lupyan, G., Oh, G. E., Paul, J., Petrone, C., Ridouane, R., Reiter, S., Schümchen, N., Szalontai, Á., Ünal-Logacev, Ö., … Winter, B. (2022). The bouba/kiki effect is robust across cultures and writing systems. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, 377(1841), Article 20200390. https://doi.org/10.1098/rstb.2020.0390

Margolis, K. G., Cryan, J. F., & Mayer, E. A. (2021). The Microbiota-Gut-Brain Axis: From Motility to Mood. Gastroenterology, 160(5), 1486–1501. https://doi.org/10.1053/j.gastro.2020.10.066